The concept of profit sharing is deeply rooted in the idea of aligning employee success with company success. It represents a powerful compensation strategy where an employer distributes a portion of the company’s annual or quarterly pre-tax profits among eligible employees. More than just a simple bonus, a well-structured Profit Sharing Plan (PSP) is a sophisticated financial and motivational tool that can significantly impact employee loyalty, productivity, and long-term financial security.

This comprehensive guide delves into what a PSP is, how it operates, the various forms it can take, the legal framework governing its use, and the profound effects it has on both employees and the organization.

What is a Profit Sharing Plan (PSP)?

A Profit Sharing Plan (PSP) is a type of defined contribution plan recognized by the Internal Revenue Service (IRS). Unlike a pension plan, which promises a specific future benefit, or a 401(k) plan, which relies primarily on employee deferrals, a PSP relies exclusively on employer contributions tied directly to the company’s profitability.

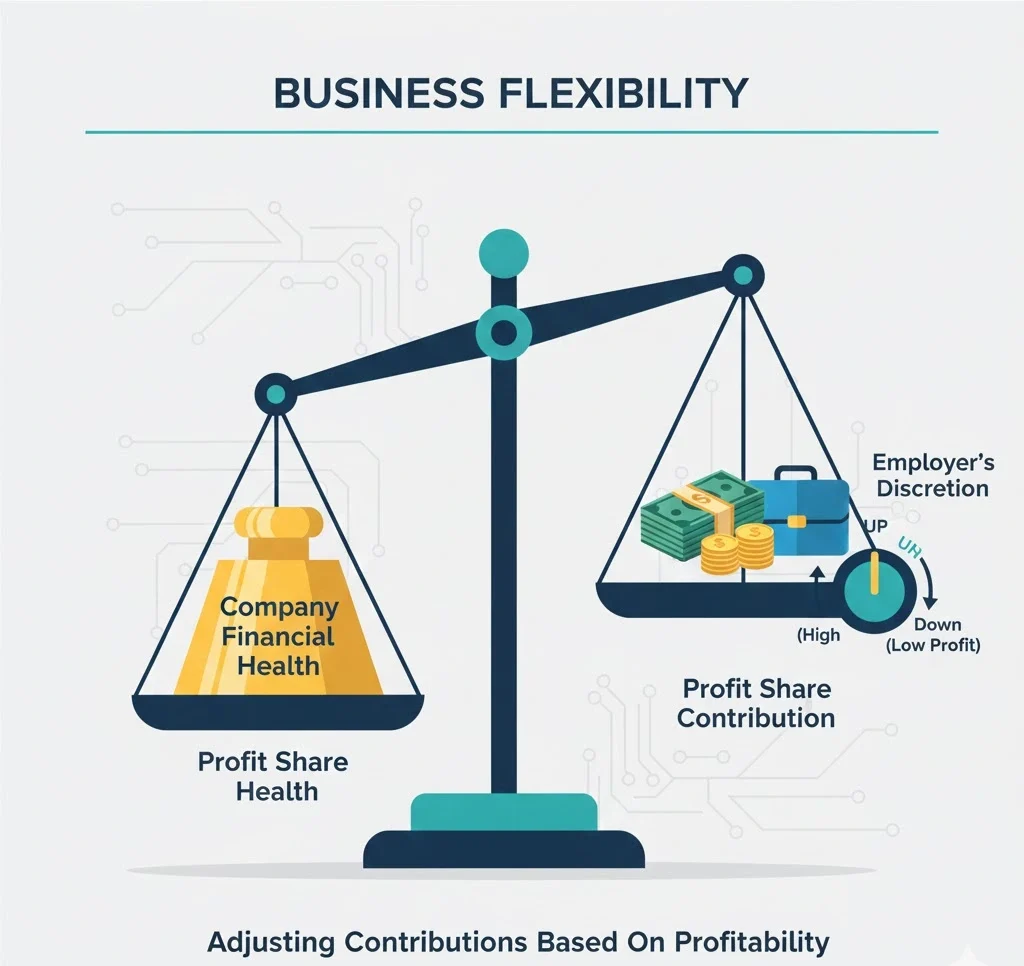

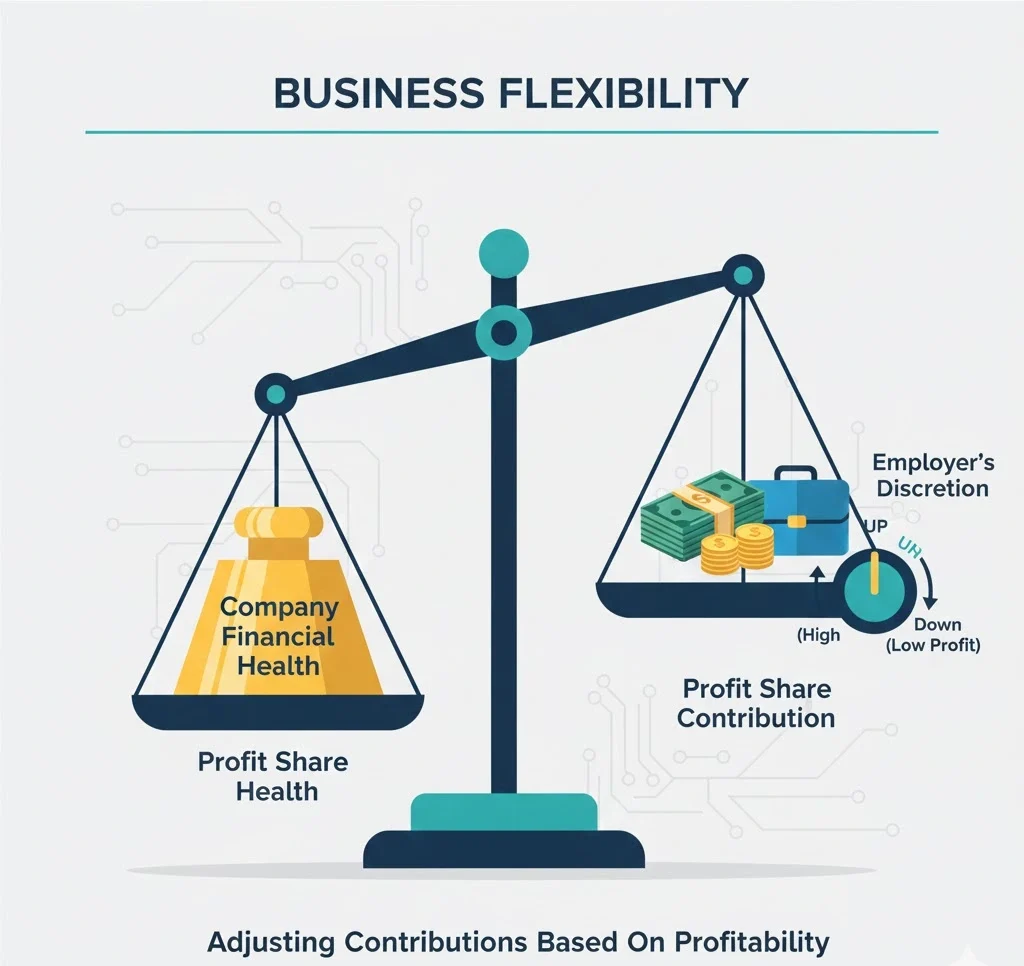

The defining characteristic of a PSP is its flexibility. The employer is not legally obligated to make a contribution every year. If the business experiences a lean year or prioritizes other strategic investments, the company can reduce or suspend the profit sharing contribution without penalty. This makes the PSP an attractive benefit option, especially for small and mid-sized businesses where cash flow predictability can fluctuate.

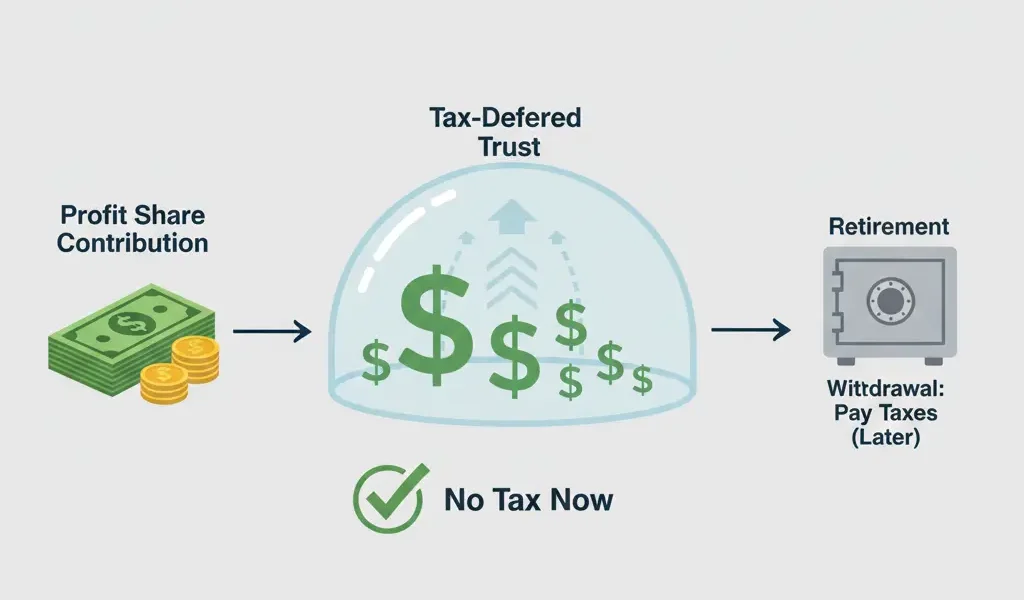

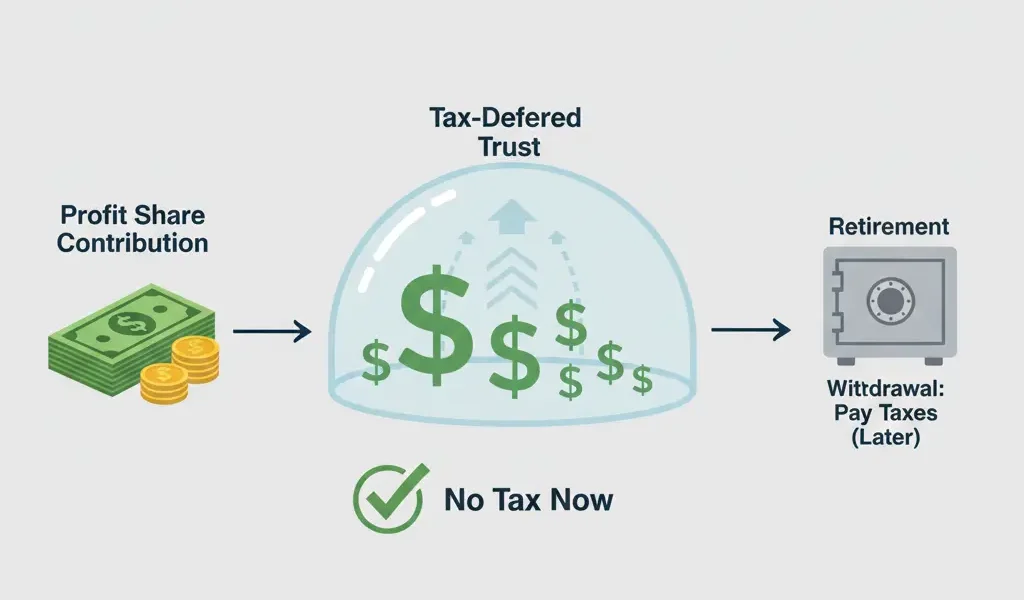

These contributions are generally held in a tax-deferred trust for the employee, typically accessible only upon retirement, separation from the company, or specific qualifying events (e.g., disability). When structured properly, the employer’s contributions to the PSP are tax-deductible up to a limit—generally 25% of the total compensation paid to all plan participants.

The Mechanics: How PSPs Are Funded and Operated

The operational flow of a profit sharing plan involves two main decisions made by the employer: the amount of profit to share and the method of allocation.

1. Determining the Contribution Amount

An employer must first establish a formal contribution formula in the plan document. However, the decision to contribute, and how much, is usually discretionary year-to-year. Common formulas include:

Fixed Percentage of Profits: The company commits to contributing a set percentage (e.g., 5% or 10%) of its pre-tax net profits above a certain financial threshold.

Formula-Based, but Flexible: The plan document states a formula, but grants the board or owner the right to deviate from that formula based on business needs.

Purely Discretionary: The company decides the total contribution amount annually, based on financial performance and strategic goals, without reference to a fixed percentage.

Regardless of the formula chosen, the maximum allowable employer deduction for contributions to all defined contribution plans (including a PSP and any other plans like a 401(k) match) is limited. For the 2025 tax year, the total amount contributed on behalf of an employee to a PSP cannot exceed the lesser of 100% of their compensation or a statutory dollar limit (e.g., $70,000, subject to change).

2. Allocating Profits to Employees

Once the total pool of money for the profit share is determined, the employer must use a defined allocation method to distribute the funds among eligible employees. The plan document must specify which of the following IRS-approved methods will be used:

A. Same-Dollar (Flat Amount) Method

This is the simplest method. The total profit sharing pool is divided equally among all eligible participants, regardless of their salary, age, or tenure.

Example: If the company contributes $50,000 and has 50 eligible employees, each receives $1,000.

Best Suited For: Companies prioritizing equality and teamwork, often those with a small, relatively flat organizational structure.

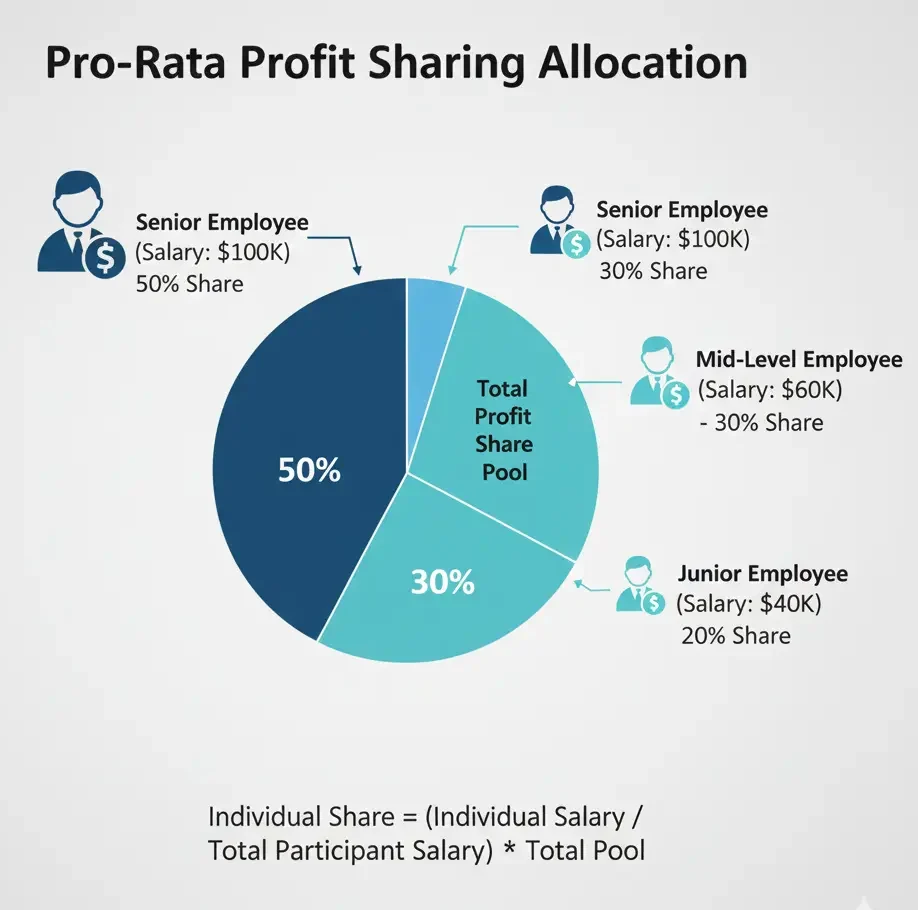

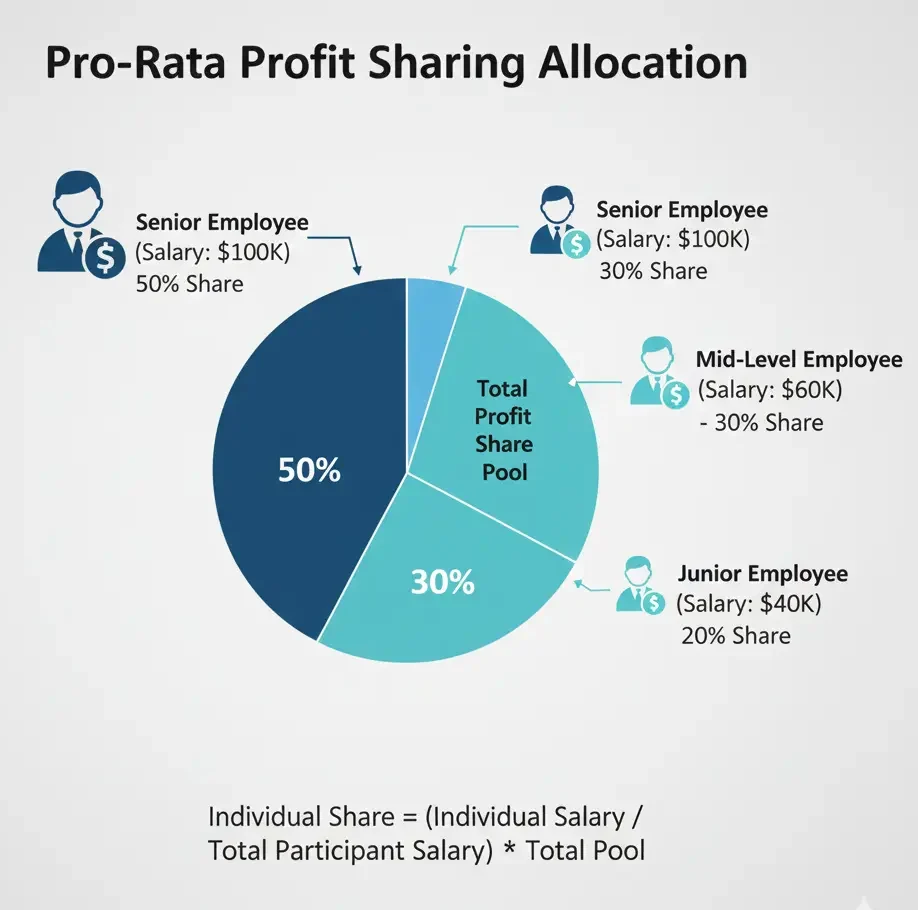

B. Pro-Rata (Comp-to-Comp) Method

Also known as the compensation-to-compensation method, this is the most common approach. The profit share an employee receives is directly proportional to their annual salary relative to the total compensation of all participating employees.

Example: An employee earning $100,000 in a company where the total payroll for participants is $1,000,000 would receive 10% of the total profit sharing pool.

Best Suited For: Companies that want to reward employees based on their established value (salary) and maintain parity with existing pay scales.

C. Age-Weighted Method

This method allocates a higher percentage of the contribution to older employees. Since older employees have less time until retirement, this method allows the company to contribute a larger sum on their behalf while still meeting IRS testing requirements for all employees.

D. New Comparability (Cross-Tested) Method

This method involves defining different classes of employees (e.g., executives, managers, staff) and setting different contribution rates for each class.

Key Requirement: Because this method can potentially favor Highly Compensated Employees (HCEs), it is subject to rigorous nondiscrimination testing by the IRS. The plan must satisfy the “minimum gateway” requirement, meaning that Non-Highly Compensated Employees (NHCEs) must receive a minimum contribution (typically 3% to 5% of their compensation) to ensure the plan benefits a broad range of employees and not just top earners.

Best Suited For: Companies seeking maximum flexibility to reward specific groups or incentivize key personnel while maintaining compliance.

Profit Sharing vs. 401(k)

While both PSPs and 401(k)s are popular retirement savings vehicles, they serve fundamentally different purposes and have distinct funding rules.

| Feature | Profit Sharing Plan (PSP) | 401(k) Plan |

| Primary Funding Source | Employer profits only; contribution is discretionary. | Employee salary deferrals; contribution is mandatory for employees who wish to participate. |

| Employee Contributions | None permitted (unless added to a 401(k) structure). | Essential feature; employees choose how much to defer (up to annual IRS limit). |

| Required Annual Contribution | No—employer can contribute $0 in a given year. | No, but an employer match is often offered as an incentive. |

| Typical Goal | Motivate performance; retain long-term employees. | Encourage employee savings; offer a foundational retirement benefit. |

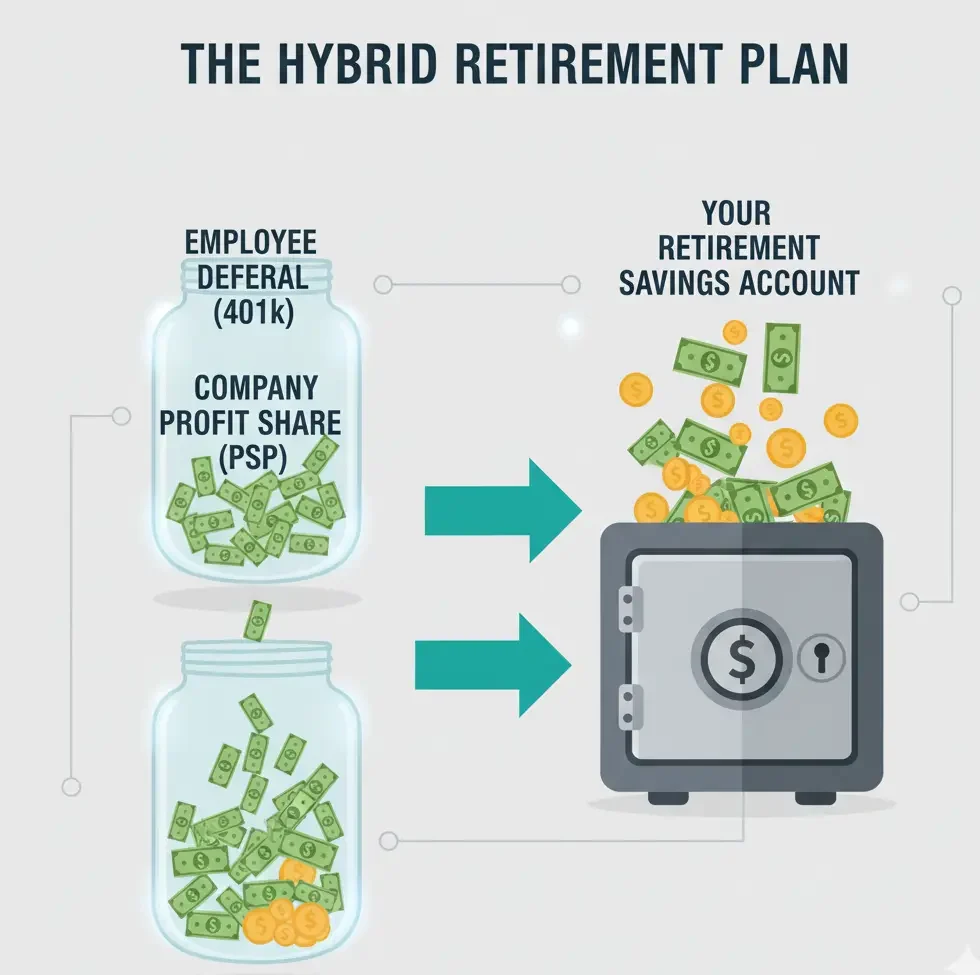

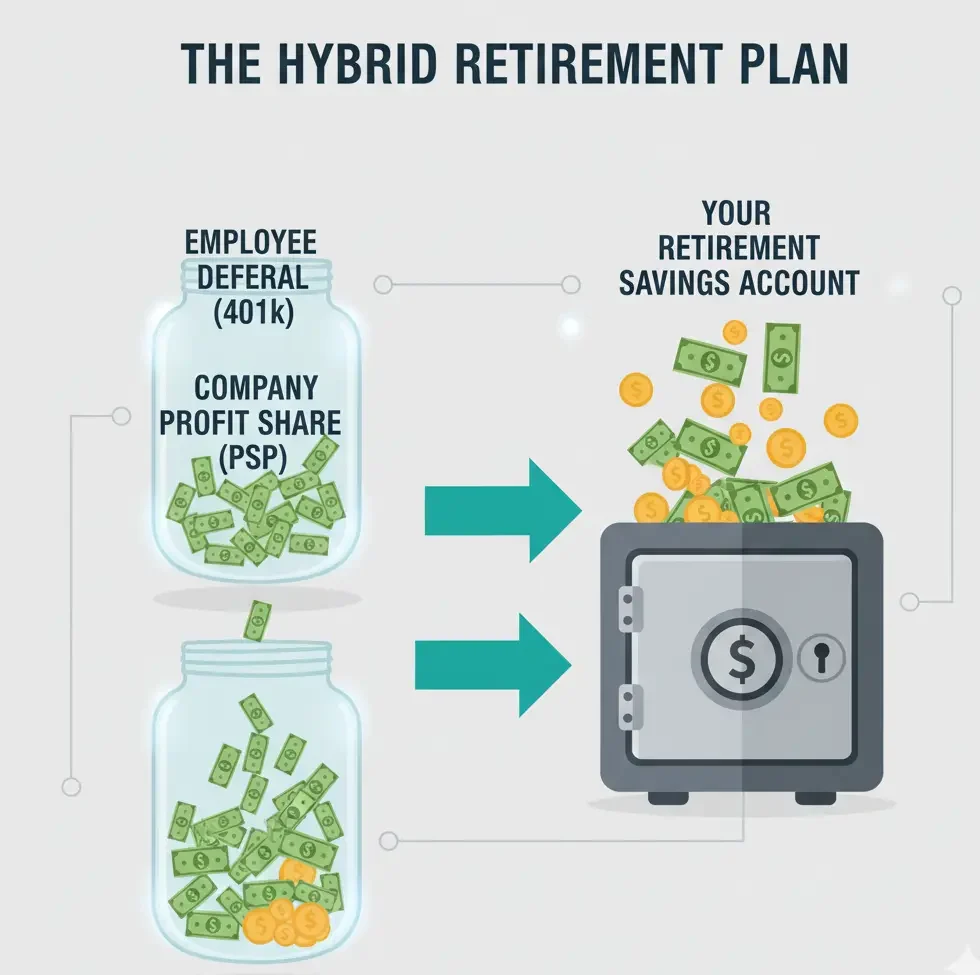

The Hybrid: Adding Profit Sharing to a 401(k)

In practice, many businesses offer a single plan that combines the features of both. This is known as a 401(k) Profit Sharing Plan. This hybrid design is extremely flexible, allowing the employer to:

Offer a standard 401(k) feature: Employees can make pre-tax (or Roth) salary deferrals.

Offer a matching contribution: The employer can match employee deferrals (e.g., 50% of the first 6% deferred).

Offer a discretionary profit share: The employer can contribute an additional, flexible profit sharing contribution on top of the match, depending on the year’s profits.

This structure allows the employer to reward employees in a booming year without committing to the expense in a downturn.

Vesting, Distribution, and Taxation

Understanding when employees gain legal ownership of the PSP funds and how those funds are taxed is crucial for both the employer and the participant.

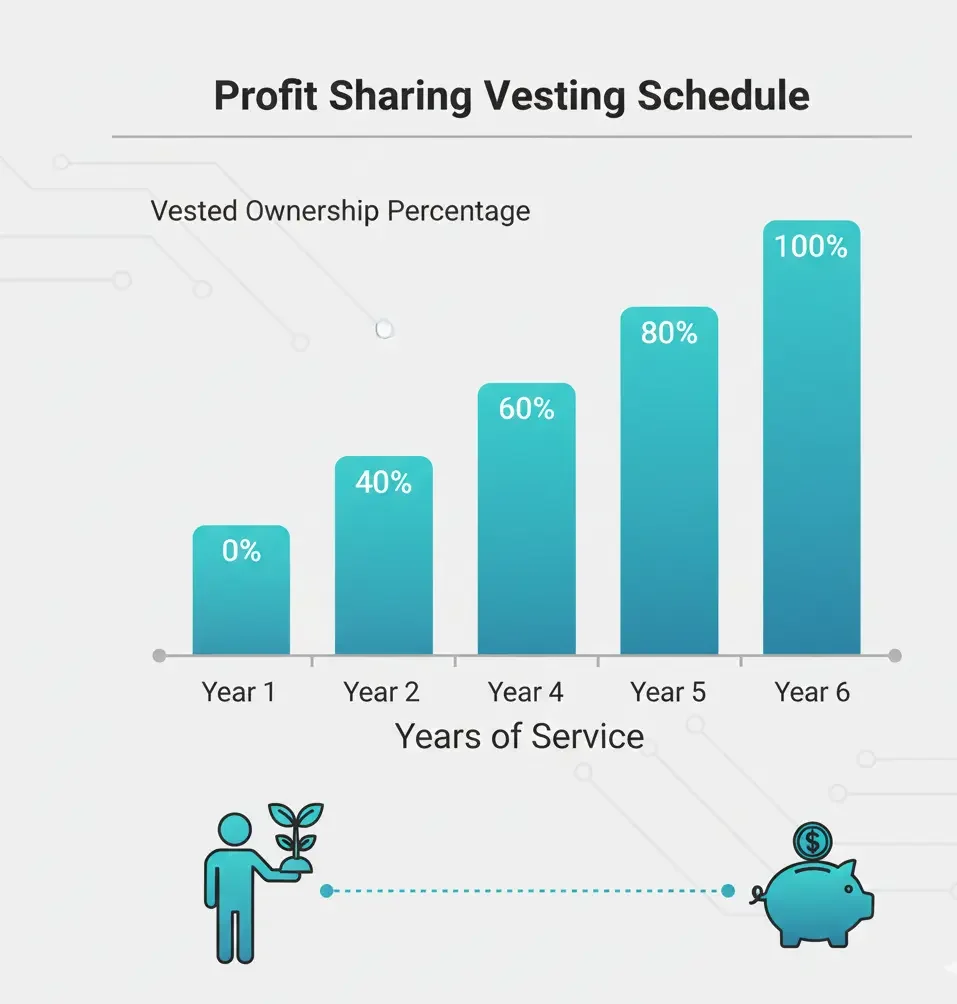

Vesting Schedules

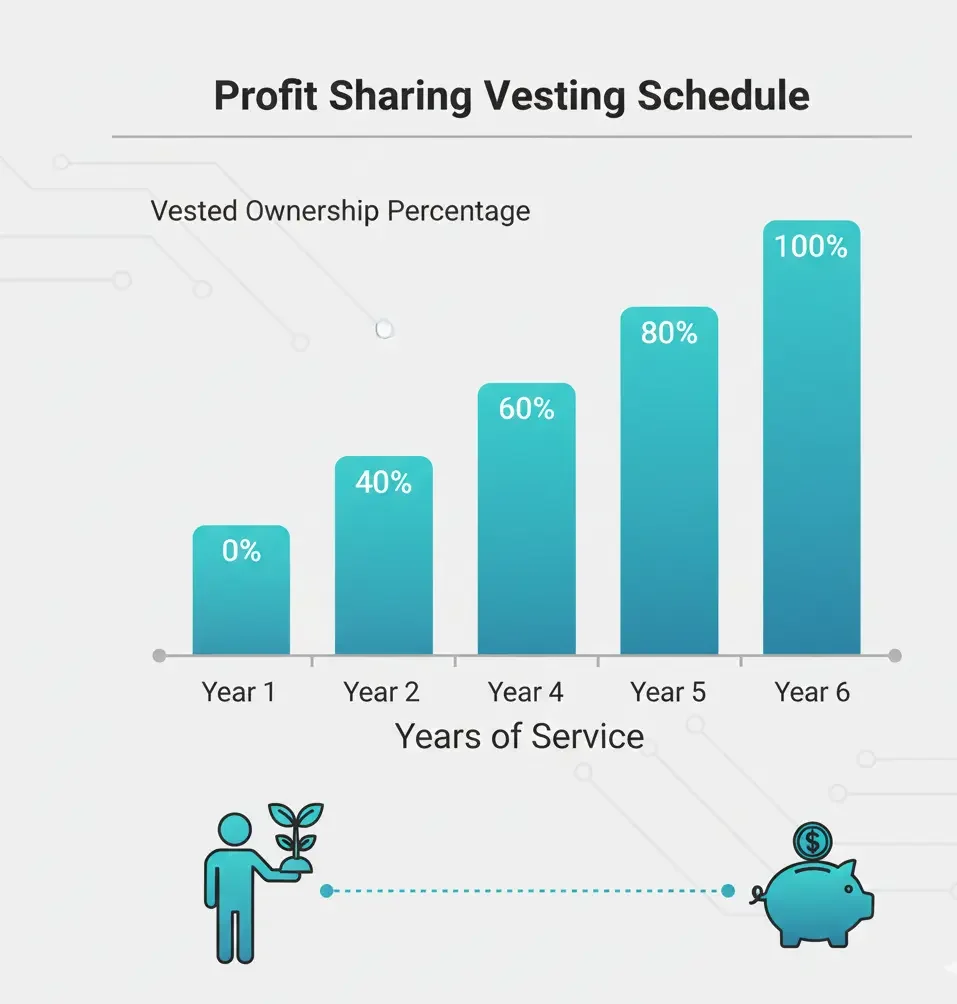

Vesting refers to the employee’s right to keep the employer’s contributions, even if they leave the company. Because the PSP is designed to encourage long-term commitment, vesting schedules are used to delay the employee’s full ownership of the funds. The IRS mandates that all employee contributions (in a 401(k) component) are always 100% vested immediately. However, employer contributions (the profit share) are subject to a schedule:

Cliff Vesting: The employee becomes 100% vested after a short, fixed period of service (e.g., two years). If the employee leaves one day before the cliff date, they forfeit all employer contributions. The maximum IRS-approved cliff schedule is three years.

Graded Vesting: The employee gains ownership incrementally over a period of time. A common schedule is 20% vested after two years, and an additional 20% each year thereafter, until they are 100% vested after six years. The maximum IRS-approved graded schedule is six years.

Any unvested funds that are forfeited by a departing employee are typically used to reduce future employer contributions or are reallocated to the remaining participants in the plan.

Distribution Rules and Taxation

Since the profit share is usually deposited into a tax-deferred retirement account, distribution generally occurs when an employee:

Separates from Service (Quits, is Fired, or Retires): The vested balance can be taken as a cash distribution or rolled over into an IRA or a new employer’s retirement plan.

Reaches Age 59½: In some plans, in-service distributions are allowed, meaning the employee can take money out while still employed.

Experiences a Hardship: Specific circumstances (defined by the IRS) may qualify an employee for a hardship withdrawal, though this may trigger a 10% penalty if the employee is under age 59½.

Taxation

Employer: Contributions are tax-deductible as a business expense.

Employee (Deferred Plan): Contributions are made on a pre-tax basis, meaning they are not included in the employee’s taxable income for the year they are deposited. The funds grow tax-deferred. The employee pays ordinary income tax on the entire amount (contributions plus earnings) only when they are withdrawn in retirement.

Benefits and Disadvantages of Profit Sharing

The decision to implement a PSP involves weighing substantial benefits against potential drawbacks.

Key Benefits

| For the Employer | For the Employee |

| Maximized Flexibility | Potential for High Returns |

| The plan is entirely discretionary, allowing the employer to skip contributions during unprofitable periods, preserving capital. | Profit sharing often exceeds typical 401(k) matches in profitable years, accelerating retirement savings. |

| Talent Recruitment and Retention | Alignment with Company Success |

| A PSP, especially one with a vesting schedule, acts as a “golden handcuff,” incentivizing long-term loyalty and reducing employee turnover. | Employees are motivated to work harder and smarter, as their efforts directly translate into higher personal retirement accounts. |

| Tax Advantages | Tax-Deferred Growth |

| Employer contributions are deductible, reducing the company’s taxable income for the year. | Funds grow tax-free until withdrawal, maximizing the power of compounding interest. |

| Nondiscrimination Testing Ease | No Out-of-Pocket Contribution Required |

| When combined with a 401(k), the PSP contribution can often be used to help the plan pass necessary IRS nondiscrimination tests. | The contribution is a “free” benefit from the employer, requiring no salary reduction from the employee. |

Potential Disadvantages

Variable Employee Expectation: In years where the company earns little or no profit, a zero contribution can lead to employee disappointment and low morale, potentially counteracting the initial motivational benefit.

Administrative Complexity: PSPs are governed by ERISA (Employee Retirement Income Security Act) and require rigorous administration, including annual non-discrimination testing, fiduciary responsibilities, and mandatory IRS Form 5500 filings.

High Costs in Good Years: While flexible, a commitment to sharing a substantial portion of profits can lead to significant expenses during boom years, potentially straining capital reserves needed for reinvestment.

How to Establish a Profit Sharing Plan

Implementing a PSP involves several critical steps that require expert consultation to ensure legal compliance.

Adopt a Written Plan Document: This document is the legal foundation of the plan. It outlines the eligibility requirements (age, tenure), the contribution formula, the vesting schedule, and the rules for distributions. This document is usually prepared by a retirement plan professional.

Arrange a Trust: Plan assets must be held in a trust, separate from the company’s operating assets, to protect them from company creditors. A trustee (often a financial institution) must be appointed to manage the trust, oversee investments, and ensure funds are used solely for the benefit of participants.

Develop a Recordkeeping System: An accurate system must be established to track contributions, earnings, losses, vesting percentages, and distributions for every single participant. This is often outsourced to a third-party administrator (TPA).

Fiduciary Responsibility: The employer is considered a fiduciary to the plan, meaning they have a legal obligation to act in the best financial interest of the plan participants. This includes prudent selection and monitoring of the plan’s investments and service providers.

Provide Information to Employees: Eligible employees must receive a Summary Plan Description (SPD), a document written in plain language that explains the plan’s rules, benefits, and rights.

Administer and Report Annually: The plan administrator must ensure continuous compliance with IRS and Department of Labor (DOL) regulations, most notably by filing Form 5500 annually.

Profit Sharing FAQs

What legal constraints limit the amount an employer can contribute?

An employer can deduct contributions up to 25% of the total compensation of all participating employees. Additionally, the maximum amount contributed on behalf of any single employee (the “annual additions” limit, which includes all employer contributions to all defined contribution plans) is subject to a statutory dollar limit set annually by the IRS (e.g., $70,000 for 2025).

Is profit sharing taxable? If so, when?

For deferred PSPs (the most common type, linked to retirement):

For cash-based PSPs (direct bonuses):

The money is treated as ordinary compensation, taxed in the year it is received, and is subject to federal income tax, Social Security (FICA), and Medicare withholding.

Do employees get profit sharing if they quit?

It depends on the plan’s vesting schedule. If an employee is 100% vested, they get the full balance of the profit share contributed on their behalf. If they are only 40% vested, they receive 40% of the account balance (which can usually be rolled over). The remaining 60% is forfeited back to the plan.

Do all employees get profit sharing?

No. The plan document defines eligibility rules (e.g., must be 21 and have worked for the company for at least one year). However, the plan must pass IRS nondiscrimination testing (the “minimum coverage test”) to ensure that it benefits a sufficient number of Non-Highly Compensated Employees (NHCEs) relative to Highly Compensated Employees (HCEs). An employer cannot simply provide the benefit only to top executives.

How often do companies pay profit sharing?

Payment frequency is defined in the plan document and varies. Contributions for deferred PSPs are typically calculated and deposited annually, often shortly after the fiscal year ends and the final profit figures are determined. Cash-based plans might be paid quarterly or semi-annually.

What is an ESOP, and how is it related to profit sharing?

An Employee Stock Ownership Plan (ESOP) is a specific type of profit sharing plan that is required by law to invest primarily in the stock of the sponsoring employer. Instead of contributing cash or other investments, the company contributes its own stock (or cash to buy its stock) on behalf of the employees. It is one of the plan structures an employer can use for profit sharing.

Conclusion:

The Profit Sharing Plan is a foundational tool in modern compensation strategy, acting as a crucial link between corporate financial health and individual employee wealth. Its inherent flexibility allows businesses, particularly small and growing ventures, to weather economic downturns without mandatory fixed retirement contributions, while simultaneously offering employees a powerful incentive to drive profitability.

By turning employees into stakeholders even if only psychologically through financial participation PSPs foster a culture of alignment, productivity, and long-term commitment. However, a successful PSP requires meticulous design, rigorous administration, and a clear understanding of its legal obligations, ensuring that this generous benefit truly serves the dual purpose of enriching the company and securing the financial future of its dedicated workforce.